Photo credit: Myra Klarman

We often hear the phrase “elections have consequences.” True enough, but sometimes those consequences fly under the radar. One example is the change in the makeup of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) that occurs when a new presidential administration takes over. That has never been so apparent as it is right now.

The NLRB is the federal agency charged with enforcing the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). Though not a prominent agency in the eyes of the general public, the NLRB has a significant impact on a major life activity of the vast majority of Americans: working. NLRB rulings profoundly affect the rights of employees in both union and non-union workplaces.

Since the Trump administration took over in early 2017, the NLRB has issued a remarkable string of rulings that are unquestionably pro-employer, and that demonstrate a willingness to overturn decades of settled law in ways that are not at all in the best interests of workers—including musicians in ICSOM orchestras.

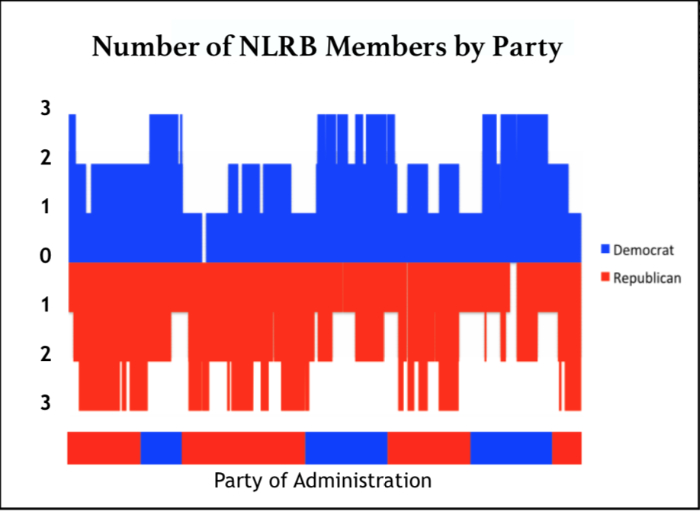

The reason for such a radical change in course is that the five Board members of the NLRB, who act as a quasi-judicial body in deciding cases that arise through NRLB administrative proceedings, are appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. They are appointed to staggered 5-year terms. In addition, the General Counsel of the NLRB, who decides which cases to bring before the Board, also is appointed by the President (to a 4-year term). A new administration, therefore, has the ability to effect wholesale change with respect to the very people responsible for both prosecuting and deciding cases that arise from disputes over the interpretation or enforcement of the federal labor laws.

Currently, the Board has only four members because no one has been nominated to replace the Obama-appointed member whose term expired in 2018. Of the four current members, three have now been appointed by Donald Trump and confirmed by the GOP-controlled Senate. Because three is the minimum number required to issue decisions, a 3–1 majority now solidly reflects the view of the Trump administration with regard to the respective rights of employers and employees. Moreover, the term of the lone remaining holdover from the Obama administration expires this month (December 2019). The current administration thus has the ability to appoint all five members of the Board.

By tradition, the President typically allows the opposing party to choose two Board members, for a 3–2 ideological split, as a way of preventing revolutionary revisions to labor law when administrations change. This is not required by law, however, and the Trump administration and Senate have shown no willingness thus far to allow the Democrats to choose any Board members. Given the current political climate and this administration’s demonstrated lack of deference to institutional norms, I expect this bipartisan tradition to fall by the wayside.

Source: National Labor Relations Board

Since the confirmation of the third administration nominee in April 2018, NLRB rulings have been coming fast and furious. Virtually all have been decided on a pro-employer basis, and many have explicitly overruled previous decisions—some from the Obama-era Board but many from well before—on no basis other than that the current Board members disagree with their predecessors. That is a significant departure from the approach of previously-constituted Boards and courts, which typically adhere to stare decisis—the legal principle of affording respect to precedent—in order to ensure stability and predictability in the law. It is rare for any adjudicator to overrule precedent simply because the adjudicator thinks the precedent is “wrong,” but that is precisely the approach of the current Board.

Below are three recent rulings most likely to have a significant impact on musicians in ICSOM orchestras.

I. Tobin Center for the Performing Arts, 368 NLRB 46 (Aug. 23, 2019)

The NLRB’s decision in Tobin Center implicates ICSOM members quite directly because, well, it involved an ICSOM orchestra. The case arose when the musicians of the San Antonio Symphony (SAS) attempted to leaflet on the sidewalk in front of their primary performance space, the Tobin Center, to protest Ballet San Antonio’s use of a recorded orchestra instead of live musicians. Tobin Center staff directed San Antonio police officers to eject the musicians from the sidewalk, which is owned by the Tobin Center (though it is open to the public). The musicians were forced to relocate across the street, where there was less patron traffic.

SAS doesn’t own the Tobin Center and doesn’t have an exclusive lease. Instead, like many ICSOM orchestras, SAS has a licensing agreement with the Tobin Center that permits SAS to use the hall for a certain number of weeks per season; other arts groups and traveling acts use the hall in other weeks. Roughly 80% of the SAS musicians’ work occurs at the Tobin Center, but as in most every orchestra the musicians perform some services elsewhere. The musicians’ status vis-à-vis the Tobin Center at the time of their protest, therefore, was that of off-duty employees of a contractor, at a time when that contractor (SAS) did not have the right to use the property.

Such a fact pattern requires balancing two important legal rights: the inherent right of a property owner to exclude persons from its property, versus the statutory right of employees to exercise their rights under Section 7 of the NLRA “to engage in . . . concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” At the time of the SAS musicians’ leafletting attempt, the legal standard regarding the resolution of those competing interests was clear: under the NLRB’s decision in New York New York Hotel & Casino, 356 NLRB 907 (2011), a property owner may exclude off-duty employees of a contractor who are regularly employed on the property only where the owner is able to demonstrate that their activity significantly interferes with the owner’s use of the property, or where exclusion is justified by another legitimate business reason.

Under that test, the Tobin Center plainly had no right to call the police on the SAS musicians. The musicians were regularly employed by SAS at the Tobin Center, and nothing about their leafletting interfered with the ballet performances. When the union filed an unfair labor practice on their behalf, therefore, an administrative law judge at the NLRB had no difficulty finding that the Tobin Center violated the NLRA when it kicked the musicians off the sidewalk.

But when the Tobin Center appealed the decision to the full Board, the new Board used that opportunity to rewrite the law. It overruled New York and created a new rule: off-duty employees of a contractor seeking to engage in Section 7 activity are “trespassers,” whom the property owner has the right to exclude from its property, unless (i) those employees “work both regularly and exclusively on the property,” and (ii) the employees have no “alternative means to communicate their message.” “Regularly” means the contractor “regularly conducts business or performs services” on the property; and “exclusive” means the employees “perform all of their work for that contractor on the property.” (Emphasis mine).

Under that new test, the Board held, the Tobin Center had the absolute right to eject the SAS musicians from the sidewalk: the musicians didn’t work “exclusively” at the Tobin Center because in the past season “only 79 percent” of their services occurred there; and they didn’t perform “regularly” at the Tobin Center because SAS was there “only 22 weeks” per season. The Board also noted that even if the musicians could have passed the “regularly and exclusively” text, they still were properly ejected because they had an “alternative means to communicate their message”—they could (and did) go across the street.

It’s a bad decision for many reasons. First, as the lone non-Trump-appointee Board member noted in her dissent, the Board was overruling clear precedent for no other reason than that the three-member majority disagreed with it. Indeed, the 2011 decision in New York had been approved by the courts: it had been enforced by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals (which hears appeals from Board decisions), and the Supreme Court had declined a petition to challenge it. No other court case or Board ruling had ever questioned it.

Second, the new legal standard is so strict as to essentially allow property owners to exclude off-duty employees seeking to engage in Section 7 activity pretty much at will. Evidently, off-duty contractor employees won’t pass the “exclusively” test unless 100% of their work is done on the property owner’s premises, and nowhere else; and it seems that “regularly” requires that the contractor have a near-constant presence on the property. The Tobin Center was entitled to treat the SAS musicians as total strangers—trespassers!—despite the fact that they performed the vast majority of their work there. Such a rule defies all common sense and affords no weight whatsoever to the rights afforded employees under Section 7 of the NLRA.

Even more absurd, the Board declared that “social media, blogs, and websites” can serve as sufficient “alternative means” of communicating a message—thus guaranteeing that there will never be an instance where employees have no alternative means. As a practical matter, therefore, the new rule announced in Tobin Center will prohibit off-duty employees of contractors from engaging in Section 7 activity in their workplace in every instance—even if they work there regularly and exclusively—simply because they can post a message on Facebook.

As a result of this decision, ICSOM orchestra musicians will need to take extra care when engaging in leafletting, performing, or other Section 7 activity. You will need to ascertain whether the sidewalk or plaza at issue is public property; and if not, you will need to find who owns it and their relationship with the orchestra. Any group contemplating such activity will need to consult with local counsel.

II. MV Transport, 368 NLRB No. 66 (Sept. 10, 2019)

In a union workplace, the NLRA requires an employer to bargain in good faith with the union over mandatory subjects of bargaining (e.g., wages, hours, and other terms and conditions of employment). Accordingly, an employer may not implement a work rule or practice that effects a material (i.e., not insignificant) change without bargaining with the union, unless the employer has been relieved of that obligation. Most often, the employer is relieved of its bargaining duty only when the union has waived its right to bargain—either through contract language or a course of conduct showing such a waiver.

For many years, as reflected in Provena St. Joseph Medical Center, 350 NLRB 808 (2007), the Board has held that any such waiver must be “clear and unmistakable.” That requires evidence that the union and the employer “unequivocally and specifically express[ed] their mutual intention to permit unilateral employer action with respect to a particular employment term.” Without that showing, the employer is not permitted to make a unilateral change.

In MV Transport, the employer unilaterally implemented revisions to certain policies and work rules. Relying on the “clear and unmistakable waiver” standard set forth in Provena, the union filed an unfair labor charge. But the Board, overruling Provena, rejected the waiver standard altogether and found all of the employer’s unilateral changes permissible. The Board decided on a new, “contract coverage” rule: an employer is entitled to make a unilateral change if the proposed change falls “within the compass or scope of contract language that grants the employer the right to act unilaterally,” based on “ordinary principles of contract interpretation.”

Translated into English, this means that instead of looking to see whether the union waived its right to bargain, the Board will now look at the CBA to see if the change is “covered by” an existing contract provision. That opens the door for employers to rely much more heavily on so-called management-rights clauses to justify unilateral changes.

Before MV Transport, management-rights clauses, which often have language permitting the employer to “promulgate reasonable rules and regulations in the workplace” (or something similar), did not support a finding of a waiver unless the rights afforded management were specific to the subject matter of the proposed change. (For example, a clause allowing management to promulgate rules regarding “on-stage decorum” would probably allow management to unilaterally implement a no-cell-phones-on-stage policy; but that would not work if the clause simply said, “reasonable rules and regulations.”) But now, under MV Transport, if a clause is interpreted so that the proposed change is “within the compass or scope” of the clause, unilateral implementation by the employer will be permitted.

As if there were any doubt that the Board intended to give employers much more authority to act under management-rights clauses, it offered a helpful example: “if an agreement contains a provision that broadly grants the employer the right to implement new rules and policies and to revise existing ones, the employer would not violate [the NLRA] by unilaterally implementing new attendance or safety rules or by revising existing disciplinary or off-duty-access policies.”

This is significant. You may be accustomed to your management coming to the union or orchestra committee if they want to change attendance rules, disciplinary policies, safety rules, or backstage-access policies. They had to, because in most orchestra CBAs, management-rights clauses (if they exist at all) are typically broadly worded and would not have constituted a “clear and unmistakable” waiver of the right to bargain over such specific rules. But now, management may not need to come to you. Depending on how the management-rights clause is written, or whether there are other provisions in your CBA granting management the right to act unilaterally in certain circumstances, your management may be able to simply tell you, “these are the new rules—deal with it.”

III. LA Specialty Produce Co., 368 NLRB No. 93 (Oct. 8, 2019)

LA Specialty Produce grew out of the Board’s 2017 decision in Boeing Co., 365 NLRB No. 154 (Dec. 15, 2017), in which the Board further upended the existing framework regarding the legality of work rules.

As noted before, under Section 7 of the NLRA, all employees—both union and non-union—have the right not only to organize, but “to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” Under the standard in place for many years before Boeing (as articulated in Lutheran Heritage Village-Livonia, 343 NLRB 646 (2004)), that meant a work rule or policy issued by an employer is unlawful if it “reasonably tends to chill employees in the exercise of their Section 7 rights.” A work rule “tends to chill” if employees “would reasonably construe the rule’s language to prohibit Section 7 activity.” The Lutheran Heritage standard applies to work rules in union and non-union workplaces alike, whether bargained for or not.

Admittedly, the Lutheran Heritage standard led to some questionable results. As interpreted by the Obama-era NLRB in particular, it pretty much prohibited employers from issuing any kind of workplace behavior rules, social media policies, or confidentiality policies with any teeth. As I discussed in my bullying and harassment presentation at the ICSOM conference in 2016, the NLRB found unlawful a whole host of rules that don’t seem all that unreasonable, such as “treat colleagues with respect” or “work harmoniously.” But because the Board had determined that those rules would “tend to chill” employees in exercising their Section 7 rights to discuss terms and condition of employment, employers were not permitted to maintain them. Board decisions under Lutheran Heritage also led to some oddly inconsistent outcomes; for example, it was unlawful to maintain a rule prohibiting “false statements,” but a rule prohibiting “gossip” was fine. (I’ve never been able to figure that one out.)

But in overruling Lutheran Heritage in Boeing and then elaborating the new standard in LA Specialty Produce, the Board has made things worse. Under the new rule, the NLRB will place employer work rules in one of three categories: rules in Category 1 are lawful; Category 2 rules require individualized scrutiny on a case-by-case basis; and Category 3 rules are unlawful. The Board’s goal is that subsequent rulings will operate to develop a kind of database of employer rules, with the categories providing guidance as to what kinds of rules are permitted.

In determining the categories, the Board will engage in a two-step process. The charging party first has to prove that “a facially neutral rule, reasonably interpreted by an objectively reasonable employee, may interfere with the exercise of [Section 7] rights.” If that showing can’t be made, that is the end of the analysis; the rule is deemed to be a lawful, Category 1 rule. If the showing is made, then the second step of the analysis requires the NLRB to balance the nature and extent of the rule’s impact on Section 7 rights against the employer’s “legitimate justifications” for the rule. If the employer’s justifications outweigh the impact on Section 7 rights, the rule is lawful and also goes into Category 1. If the employer’s justifications do not outweigh the impact on Section 7 rights, the rule is unlawful and goes into Category 3. If it could go either way, then it is a Category 2 rule and will require “individualized scrutiny” of how the rule might be applied on a case-by-case basis.

Here is how this will play out: virtually every employer work rule will now fall into Category 1 (lawful) at either the first or second step of the process. At the first step, the current, pro-employer Board will simply find no proof that the rule would interfere with Section 7 rights when “reasonably interpreted by an objectively reasonable employee.” End of story. But even if the analysis proceeds to the second step, any balancing of the rights of employees and the “legitimate justifications” of employers will obviously have a thumb on the scale under the current Board (as evidenced by the way the Board in Tobin Center, discussed above, balanced the interests of the Tobin Center against those of the SAS musicians).

LA Specialty Produce demonstrated this in remarkable fashion. There, the employer’s confidentiality and media contact rules were challenged. Regarding the confidentiality rule, the Board found that it was unnecessary to even reach the balancing test because the hypothetical “objectively reasonable employee” would not interpret the rule so as to interfere with Section 7 rights at all. That’s questionable enough; but it is the Board’s analysis of the media contact rule that is particularly revealing and will impact ICSOM musicians.

The employer’s media rule stated that “employees approached for interview and/or comments by the news media cannot provide them with any information” and designated a management person as “the only person authorized” to comment “on Company policies or any event that may affect our organization.” Under the old Lutheran Heritage standard—and even under the new Boeing standard—this rule should have been thrown out immediately, as it (on its face) would prohibit employees from discussing anything with the media, including all subjects relating to their employment. It is difficult to imagine a more blatant Section 7 violation. But the Board again approved of the rule at the first step of its analysis, holding that the mythical “reasonable employee” would interpret the rule to prohibit employees only from speaking “on the [employer’s] behalf.” If it seems that the Board simply pulled the “on the employer’s behalf” language out of thin air, that’s because it did—that language appears nowhere in the employer’s rule.

What this shows is that when the adjudication of whether a work rule is lawful turns on the imagined interpretation of a “reasonable employee,” the adjudicator will reach the desired result simply by conjuring up their own preferred image of that hypothetical employee. The legal test can therefore be manipulated to reach a predetermined result, every time. The current pro-employer Board that wants to uphold employer’s work rules will imagine a sophisticated, conservative employee who understands his or her place in the organization and appreciates the business interests of the employer; a more pro-employee Board will imagine a worker who is hesitant to speak their mind about the workplace out of fear of violating a rule and getting fired.

Managements in some of our ICSOM orchestras have tried to implement (or bargain for) media-access rules, non-disparagement policies, social-media policies, and the like. For the most part, it has not been difficult to turn back these efforts, either on grounds that the rules must be bargained for or that they violate Section 7 rights. But under LA Specialty Produce, it seems that such rules will be interpreted in whatever way will serve to uphold them (even if it means making up new language and pretending it was in the rule all along). At a time when ICSOM musicians are trying to build their own identity and reach out to their audiences and patrons, there are some managements who may be all too eager to stifle those efforts—and now they have a sympathetic federal agency that will help them do it.

We will have to see how this all plays out. But when you hear the phrase “elections have consequences,” think of these rulings. The consequences are more direct, and more personal, than most people imagine.

Note: the author is ICSOM General Counsel.

[…] the political and legal climate for unions is more fraught than ever—just read Kevin Case’s piece about recent NLRB decisions (page 3) to get an idea. And as we in the union movement struggle to protect and build on gains […]