Photo credit: Scott Suchman

We in the National Symphony Orchestra live in a city of politicians and diplomats; they populate our neighborhoods and our audience. We play in a venue named not for a donor but for a statesman, John F. Kennedy. Despite our name, we have no official government role, of course. But the NSO’s visit to Russia in late March of this year, during a troubled period in US-Russian relations, had the feel of cultural diplomacy. We also connected powerfully with our orchestra’s own past.

The first American orchestra ever invited to take part in the annual Rostropovich Festival, the NSO gave two concerts at the Moscow Conservatory and one in St. Petersburg’s Great Hall. Olga Rostropovich, Mstislav (“Slava”) Rostropovich’s elder daughter and the founder and director of the eight-year-old Rostropovich Festival, said it had long been her dream to bring “my father’s orchestra” to honor his 90th birthday at the Festival. (The NSO was the first American orchestra Slava conducted, in 1975, and from 1977–1994 he was our Music Director. He died in 2007.) She was delighted that, when approached two years ago, the NSO agreed without hesitation, expressing no concern about election outcomes or logistical challenges.

The orchestra’s two previous Russia visits did entail challenges. In 1990 Slava brought the NSO with him for his high-profile homecoming concerts, after sixteen years of exile from his homeland. Our rooms at the Soviet-era Rossiya Hotel featured scratchy toilet paper, roaches, and nibbling mice. Instruments were damaged at customs, and the quality of the concerts suffered under the broiling TV lights and the constant click of cameras; during one concert Slava angrily shooed away a distracting videographer with his bow. But the rewards eclipsed the challenges. We were moved by the Russians’ refreshing passion for classical music. Rumors spread that students had spent all night hiding in bathrooms at the Moscow Conservatory in hopes of hearing the next morning’s rehearsal. Those without tickets scaled walls to peek through the high windows. The exuberant audience response—the glowing faces, the throwing of roses, the rhythmic clapping that would not relent until we gave yet another encore—created powerful memories.

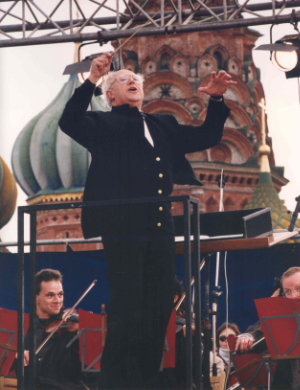

Three years later came another unforgettable milestone: The Coldest Concert Ever. In October 1993, during Slava’s final season as Music Director, the NSO became the first orchestra in history to perform in Red Square. On a makeshift platform in front of St. Basil’s Cathedral, we played the 1812 Overture in 40-degree weather. Before fingerless gloves were a fashion statement, we created them out of necessity. Woodwind players struggled to keep their instruments in tune, but the tens of thousands of listeners (including one Boris Yeltsin) who packed the massive square applauded fervently. Bells rang out from behind the Kremlin walls. Journalists hailed the event as “a symbol of liberty.”

On those earlier Russian tours, Slava was arguably the main attraction. At one concert, the musicians left the stage after several encores, including our signature Paganini Moto Perpetuo (performed in unison by both violin sections, standing). As we packed up our instruments, Slava and his baton took repeated solo curtain calls. On our recent visit, despite Slava’s having forever “left the stage”, the orchestra still experienced a strong connection to the Russian audiences.

The choices of this year’s tour repertoire resonated with our history. We opened each concert with Tobias Picker’s Old and Lost Rivers. Music Director Christoph Eschenbach wanted to present a contemporary work, as Slava—both as cellist and conductor—tirelessly championed living composers. Our two programs included, unsurprisingly, two cello concertos, the Shostakovich First and the Elgar, with soloist Alisa Weilerstein. Shostakovich had written the former in 1959 for Slava, who learned it at his dacha in three days, according to his daughter Olga. Slava premiered the concerto in the same Moscow hall where we performed it. Our second half featured either Schubert’s “Great” C Major Symphony or Shostakovich’s Eighth Symphony, the piece we took most often on our international tours with Slava.

This year, despite a few logistical blips, we once again experienced the Russians’ gratifying devotion to music. Load-in to the cramped backstage areas taxed our indefatigable stage crew. Errant lighting in Moscow left conductor, soloist, and the first stand of violins in the dark for part of a concert. But in St. Petersburg, the audience crushed in the moment the doors opened. Patrons stood five deep at the back of the hall for the duration of a 70-minute symphony. Local critics gushed that “[the NSO] performed with a virtuosity that eclipsed even the most respected of Russian orchestras” and lauded our “deep understanding of the music.”

Long-time players were particularly pleased to see reviews praise the orchestra’s “extreme sound contrasts.” Dynamics for Slava were never mere letters on a page; they always carried both emotion and imagery. To Slava, ff meant not only fierce and ferocious but also, famously, “like fork in brain.” When we see pp, we can hear him whispering, “like shadow.” These traditions remain alive, spreading to our new members each time we perform Russian music.

Throughout the week the twenty-five or so veterans of the earlier Russian trips encountered nostalgic reminders of the Slava era.

In the imposing hallways of the Moscow Conservatory, the hundreds of photos on display honored the breadth of Slava’s career and influence. NSO members spotted their younger selves in numerous shots taken during his 17-year tenure in Washington. An especially “striking” photo showed Slava marching on the picket line, arm in arm with his beloved musicians, in 1978.

The timing of our trip allowed many musicians to visit a downtown plaza that was dedicated to Slava just this year. Beneath the recently unveiled statue of the cellist hard at play, birthday flowers crowded the pedestal, which bore etchings of the opening notes of the Shostakovich cello concerto.

During a morning off in Moscow, several NSO musicians visited the Novodevichy Convent and Cemetery, where we paid our respects at the gravesite of Slava and his wife, Galina. We also visited the modest grave of Dmitri Shostakovich. Carved in relief on his tombstone was a musical staff containing four notes, his musical signature (D-Es-C-H); under Slava many of us recorded and toured with the Tenth Symphony, which celebrates that series of notes.

NSO Musicians Cindy Finks, Lisa Emenheiser Sarratt, the Author, Steve Honigberg, Hyun-Woo Kim, Alice Weinreb, Bob Oppelt, and Desi Alston pay their respects at the gravesite of Rostropovich

Photo credit: Scott Suchman

The “Salute to Slava” continued upon our return to Washington. Immediately following our trip, James Conlon led the NSO in a program of works by Britten, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich, all key figures in Slava’s musical life. We dedicated the week’s concerts to the victims of the deadly explosion that took place in the St. Petersburg metro the day after our departure from that city.

Just as Shostakovich’s works sometimes carried coded messages and multiple layers of meaning, the NSO’s visit to Russia this year implicitly offered a harmonious counterpoint to international tensions.

Note: The Author is a violinist in the National Symphony Orchestra