More than most we meet in our daily lives, orchestral musicians are blessed with a direct connection to those who came before, be they teachers, performers, conductors, or composers. Less directly, we are also tied to many other individuals from history: poets, painters, noblemen, emperors, and religious figures. Some may think, and we often hear, that our ties to the past are indicative of a dead art, a museum filled only with works whose relevance has long ago waned.

Quite the opposite is true. The rich tapestry that our past has woven is tangible evidence of the depth of music’s connection to the very soul of humanity. It is that connection to our inner being that makes music relevant. It is also why great art can affect people from different backgrounds, different social standings, different educational levels, and different cultures, in much the same way.

Our duty as artists, whether we perform an old or a contemporary piece, is to connect with the listener in a fundamental way. If we are not able to do that, our performance is irrelevant as art no matter when the music was composed. If we do connect, the audience understands the relevance and expresses it through their applause. I doubt there is a performer on stage who does not feel the energy of the audience’s reaction after hearing a truly great composition.

Change is a part of life, and, last anyone checked, we and our audiences are all living, breathing, contemporary beings. Because of that, how we as performers connect with our audiences must differ from how performers did long ago. But what it is we connect to remains fundamental to the human spirit.

What then of the charge that we are museum pieces? Why does this sentiment seem to resonate with so many? One answer is that art is not for everyone and that, unless a listener is a sensitive individual who is open enough to allow a connection to music, that listener can never appreciate the value and relevance of music. But this is an insufficient answer. There are those who appreciate contemporary art forms, including sculpture, painting, poetry, plays, and even music, who say they have no interest in symphonic music. To them, the very sound of an orchestra may itself cause a strong negative reaction. We see such attitudes whenever we must argue for funding and support within our communities. Regrettably, we too often see such attitudes expressed in print.

How, if we wish more people to appreciate our music, can such strong reactions be overcome? If we fundamentally believe that our art is relevant and connects deep within people—something that helps them connect with something they themselves value—we will not spend our time and energy trying to force our view on others and attempting to ensure that potential audience members agree that we offer something valuable.

We have but two avenues available. The first is what each of us does: perform our music well. Of course, there is always room for improvement—from musicians, from conductors, from venues, from board and management support, and so on. But we all know that quality does make a difference. It is in our endeavor to perform well that we disprove the notion that ours is a dead art, for each time we perform, it is a new performance created by the individual efforts of live musicians, manifested by the totality of all forces coming together in the hall and emanating from all the performers and audience members in attendance.

That is why recorded music, although it has its value, does not usually touch people in the same way as live performances. Think back upon those performances that have touched you the most. How many of them still evoke a feeling of fondness for or other strong connection to the performer(s)? Is the same true for recorded performances you have heard? To press the point further, what would be the reaction of an audience to a performance where they sat and listened to a performance recorded the night before, or to an orchestra performing behind a curtain that severed the audience’s connection to the performers?

I realize that what I am saying is news to no one who appreciates music. So what of the second avenue? Again, I doubt it will be news to you. We must spread the word that there is something valuable in what we do in a positive, influential, and pervasive manner. This is not to argue the point to people, but rather to let them know what it is we do in an engaging way. If marketing can sell unnecessary and even harmful products to consumers, think of what a tool it could and should be for a product that people think makes their lives better. To be effective, though, our story cannot be told in one way or by one means. While our music interpretations are linked to the past, we must find relevant ways to communicate the importance of what we do to our contemporary audiences. We cannot expect ads that simply announce our performances and their contents to attract people who have never heard a Beethoven symphony.

The message must be everywhere present, and it must be told by those who believe most in the message: the audience and the musicians (including the live composers). The message must be of an emotional nature that evokes a desire to experience whatever it is those telling the story are so excited about. Also, the message should not be spread only by paid marketing. We must find ways to make people so excited about what they experience at concerts that they become our ambassadors within our communities.

Throughout what I have said thus far, I hope two principles stand out clearly. The first is that we should embrace the past and all it brings to the present. The second is that we must not be afraid to look for new solutions to our problems. Taken together, these principles lead us to another one: When we are looking for new solutions, we must remain mindful of the past. We should not throw away everything we know just to be different. Even when Schönberg invented atonal music, it was done in a historical context, as a reaction to what came before, with the goal of creating more of what had always been valued: music that connects with people. Playing to large pops audiences may help fund the core of what we do, but it can never substitute for it.

When translated to the nonmusical activities our orchestra committees now perform, the same principles apply. Even when today’s problems bear a striking resemblance to those of the past, new solutions suited to today’s world may be necessary. At the same time, we should always be mindful of what has come before, what has worked, what hasn’t, why different solutions were tried, and why they did or did not work.

This brings me, albeit in a roundabout way, to why I am writing this article: a newly published book by Minnesota Orchestra violinist Julie Ayer. The book, More Than Meets the Ear: How Symphony Musicians Made Labor History, is a history of us and of our industry. It chronicles the evolution of the American orchestra. It takes us from our meager beginnings to today, when more orchestras than ever before are able to provide a living wage to more musicians than ever before. As such, it is also a history of ICSOM and its founders.

This brings me, albeit in a roundabout way, to why I am writing this article: a newly published book by Minnesota Orchestra violinist Julie Ayer. The book, More Than Meets the Ear: How Symphony Musicians Made Labor History, is a history of us and of our industry. It chronicles the evolution of the American orchestra. It takes us from our meager beginnings to today, when more orchestras than ever before are able to provide a living wage to more musicians than ever before. As such, it is also a history of ICSOM and its founders.

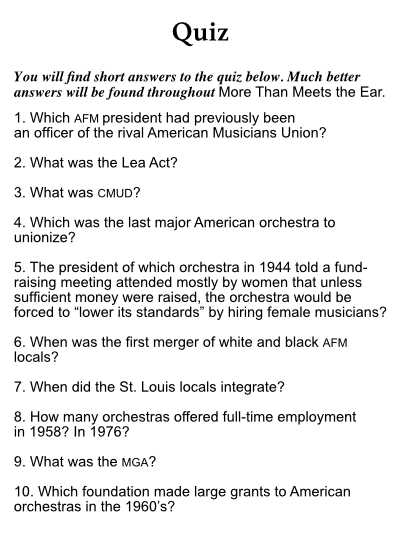

One must admire the research that went into this book. Although I consider myself fairly well versed in the history of American orchestras and the problems musicians have overcome, I was appalled by my lack of knowledge of many of the topics Julie covers. If you’d like to test your own knowledge of our history, I’ve compiled a short quiz. I’ve included answers, but I hope they will stimulate you to read the book, which really does give these and many other subjects the full treatment they deserve.

For all the history it covers, More Than Meets the Ear does not read like a dry history book. It is full of interesting anecdotes and amusing stories. Some of the pictures are heartwarming. There are many quotes—from orchestra musicians, conductors, managers, negotiators, and critics. There are also stories written from Julie’s own personal perspective, both as a violinist and as someone with interesting connections to other notable musicians.

Some of the book is devoted to the Minnesota Orchestra. You will read about Minnesota’s tours, its recordings, and its labor negotiations. It is illuminating to notice how many of the struggles the Minnesota Orchestra faced during its growth have recurred in other orchestras at other times. Contract terms that we now take for granted as foundations of our current contracts are reflections of other struggles faced by orchestras, including Minnesota, in the past. When the issues discussed pertain mainly to the Minnesota Orchestra, Julie has interspersed many comments from negotiators and orchestra musicians about the negotiations and about interesting episodes that occurred during the seasons.

For those who need convincing that the past is relevant to the present and that the battles fought before are in many ways the same battles faced today, I offer excerpts from a 1928 Chicago Daily News editorial (Julie’s book has the complete version):

Ten months ago The Daily News by appealing to friends of the Chicago Symphony orchestra raised a fund of $30,000 which helped to give another season of useful life to that fine organization….Nothing, however, seems to have been done since then to prevent a recurrence of the controversy over the orchestra’s minimum wage scale. No guaranty has been provided, no additional endowment has been obtained by the orchestral association,…and no additional use of the orchestra to furnish increased revenue has been arranged for. Consequently the association asserts once more that it cannot meet the musicians’ demand for a minimum weekly wage of $90. So it appears to have decreed the dissolution of the orchestra, one of the best in the world and for many years an intellectual and artistic necessity to Chicago’s host of music lovers….It seems clear, however, that the association’s effort to retain the minimum wage scale of two years ago is unreasonable. The controlling members of the association are singularly self-centered while they hold the fate of the orchestra in their hands. It is not their orchestra to dispose of as they please. They occupy a position of trust, administering…a semipublic institution….The statement of the orchestral association that its failure to rent Orchestra hall justifies its refusal to give its musicians the wages they ask is no suitable response to the union’s demand. Manifestly it is unfair to make the members of the orchestra suffer for a failure in management. The orchestral association faces serious problems with which its management seems unable to cope….[M]any friends of the orchestra are ready and anxious to support intelligent and effective leadership such as is required in the existing emergency. If the present directing heads…fail to solve the problem…it may be assumed that a reorganized body will provide properly for the future of the orchestra through effective administration and, if necessary, through open solicitation of an increased endowment. It would be a great pity, however, if there should be even a temporary disbanding of the splendid corps of highly trained musicians…

More Than Meets the Ear is an important book for our field. There is a wealth of information that helps us understand our roots and how we arrived where we are today. Orchestra committees would be well advised to offer a copy to all of their colleagues, and especially to their new ones, as an understanding of what and who came before can greatly increase the unity necessary when today’s orchestras face their own inevitable struggles.

Quiz Answers:

1. James C. Petrillo (also known as the “Little Caesar”).

2. Federal legislation, largely against the AFM and its president, James Petrillo, passed in 1946. Also known as the “anti-Petrillo act,” it was declared unconstitutional in 1947.

3. The Chicago Musicians for Union Democracy was started in 1961 by members of Chicago’s Local 10 to fight the autocracy of their local and its president James Petrillo. Because of the mistreatment Chicago Symphony musicians received from Petrillo and their local, many CSO musicians joined CMUD.

4. The Boston Symphony Orchestra, in 1942.

5. Boston.

6. 1953, in Los Angeles.

7. 1971.

8. None, but Boston Symphony was the closest, with 46 weeks of employment in 1958. By 1976 there were 11 52-week orchestras.

9. The Musicians Guild of America was a rival union to the AFM formed in 1958 by recording musicians. Its success was largely responsible for the end of Petrillo’s tenure as AFM president.

10. The Ford Foundation.