For many years there has been tension between individual orchestras and the AFM on issues related to electronic media. The issues are numerous and complex. After thinking about these issues over a long period of time, I have concluded that they can be boiled down to this one basic question: Should national symphonic media agreements be abandoned?

All of us know that, today, the orchestral recording market internationally is a mere shadow of what it once was. Unless there is a new revolution in technology equal to the introduction of the Compact Disc, or unless there is a cultural shift internationally in musical preferences, the market will not be revived. In spite of this fact, media exposure remains a vital necessity to those orchestras whose fame and relatively good fortunes are, in large part, due to the critical acclaim (not volume of sales) achieved through their media activity. The Cleveland Orchestra and the Philadelphia Orchestra, along with many others, are known worldwide primarily because of their recordings and broadcasts. Such international recognition makes it far easier for them to build and sustain local support in the form of ticket sales and contributions.

In general, for decades smaller orchestras have wanted to negotiate their own media agreements because most of them cannot afford the rates called for in the national agreements. At the same time, larger orchestras have wanted to uphold and maintain national agreements in part because those agreements protect against the real danger of direct competition among orchestras, which would inevitably result in a “race to the bottom” with regard to pay scales.

Given the above facts, it is somewhat understandable but also quite ironic that the members of the Cleveland and Philadelphia orchestras agreed to accept contractual terms that directly undercut existing national media scales and thus directly violate AFM bylaws—with the blessings of the AFM locals that represent them and perhaps some national officers.

Our nationally elected AFM officers are duty bound to enforce those bylaws. As such, they are required to investigate and if necessary, punish any and all members and local officers in both cities who may be responsible. In reality though, because these two cities possess a great deal of political power at AFM conventions, any national officer who wishes to be smoothly re-elected will likely take no action against those members or local officers whatsoever.

So where does this leave us? Officially we are required by AFM bylaws to uphold the national media agreements, which the AFM has negotiated on our behalf at great expense. In reality, it has been recently demonstrated that locals can in fact negotiate their own media agreements without fear of reprisal by our nationally elected AFM officers.

Has the time come for AFM bylaws to reflect reality? Should every orchestra be permitted to negotiate its own media agreements as Cleveland and Philadelphia did?

These are critical questions that must be answered. When some orchestras are passively allowed this freedom while others uphold the bylaws, serious divisions are the result.

Regardless of whether you favor national media agreements or locally negotiated agreements, we must together agree on which way to go and have the strength and courage to uphold and enforce our collective decision, regardless of political considerations. If we fail to deal with this one basic question, the divisions between orchestras and the AFM will deepen with potentially disastrous results.

Douglas Fisher is a bassoonist with the Columbus Symphony Orchestra and President of the Central Ohio Federation of Musicians, Local 103 AFM.

[Editor’s Note: The above letter was submitted for publication well before the media summit that took place in Chicago on February 21, 2005. When it became apparent that this issue would be delayed, the letter was published on Orchestra-L in advance of the media summit, where it prompted thought and discussion. Expect to read more about the media summit in the next issue of Senza Sordino.]

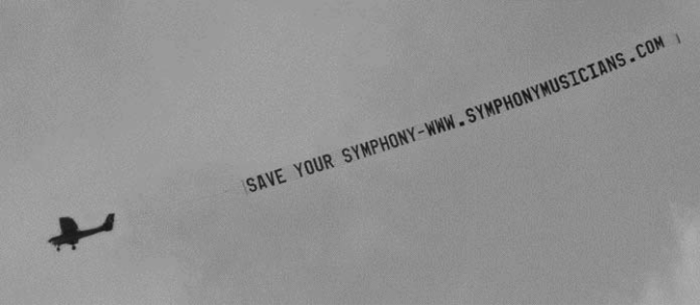

Columbus Symphony musicians get creative in advertising their highly touted Web site.